August has an older sister, Jedda, who is a ghostly presence in the novel: she disappeared while still a schoolgirl, when August was only nine. In Poppy’s dictionary the reader is allowed to glimpse the deep time which, for tens of thousands of years, fed and nourished the lives of the Wiradjuri. Taken together, these three narratives offer a layering of time. He determines, at the end of his life, “to tell how wrongs became accepted as rights”. Though for three decades he has laboured “to ameliorate the condition of the Native tribes”, he comes to perceive that government policy – to eradicate native languages, to separate children from parents and worse – visits evil on the people he came, as he believed, to serve. Greenleaf is a missionary working among the people of Massacre Plains who sees that his presence is not benign. The third narrative is provided through letters written by the Reverend Ferdinand Greenleaf in 1915 to a Dr George Cross of the British Society of Ethnography. Poppy’s dictionary may hold the key, and August is drawn into the local resistance, experiencing a growing sense of reconnection to the place in which she grew up.

One way to keep the mining company away would be to prove the current residents’ “cultural connection” to the local area or “country”, as Indigenous Australians say. There is a proposal to build a tin mine, two kilometres wide and 300 feet deep, another scar on a land already scarred for centuries: it’s enough to know that August and Poppy’s hometown is called Massacre Plains, named for reprisals against the Indigenous people who attempted to defend their land.īathurst Plains, New South Wales, where Wiradjuri people were massacred in 1824.

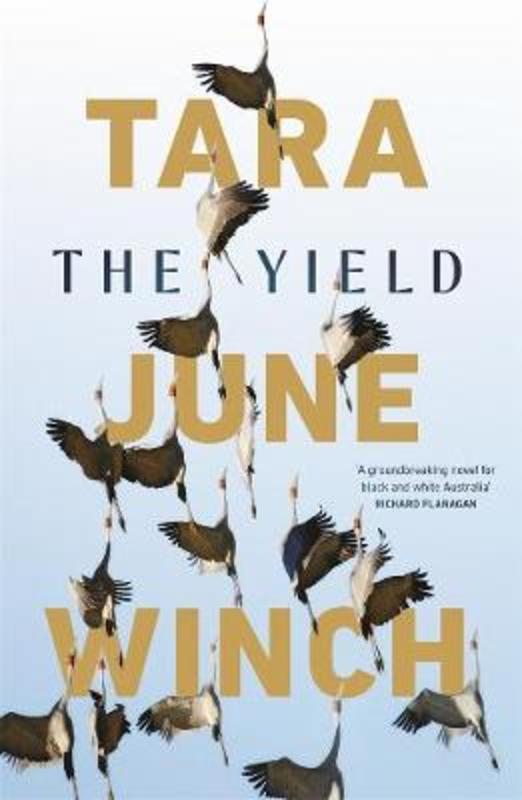

She has left Australia for England but decides to return for his funeral when she arrives, she finds that their community is under threat. August is Poppy’s granddaughter, “about to exit the infinite stretch of her twenties” with “nothing to show”. Laced into this rich catalogue of words, each one offering a glimpse of a civilisation that the colonisers of the land worked so hard to eradicate, are two other narratives. There is suicide – balubuningidyilinya house or dwelling place – bimbal, ganya eternity, things to come – girr. Poppy’s dictionary runs through this novel, with English words given their Wiradjuri translations after each translation comes a brief glimpse of how the word links to family, to land, to story. It is an effort that is being recognised when The Yield was published in Australia in 2019, it won the Miles Franklin award, Australia’s most prestigious literary prize. This is Winch’s second novel: she is herself of Wiradjuri heritage, and an afterword makes clear how significant it is for her to give that heritage a place in wider culture.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)